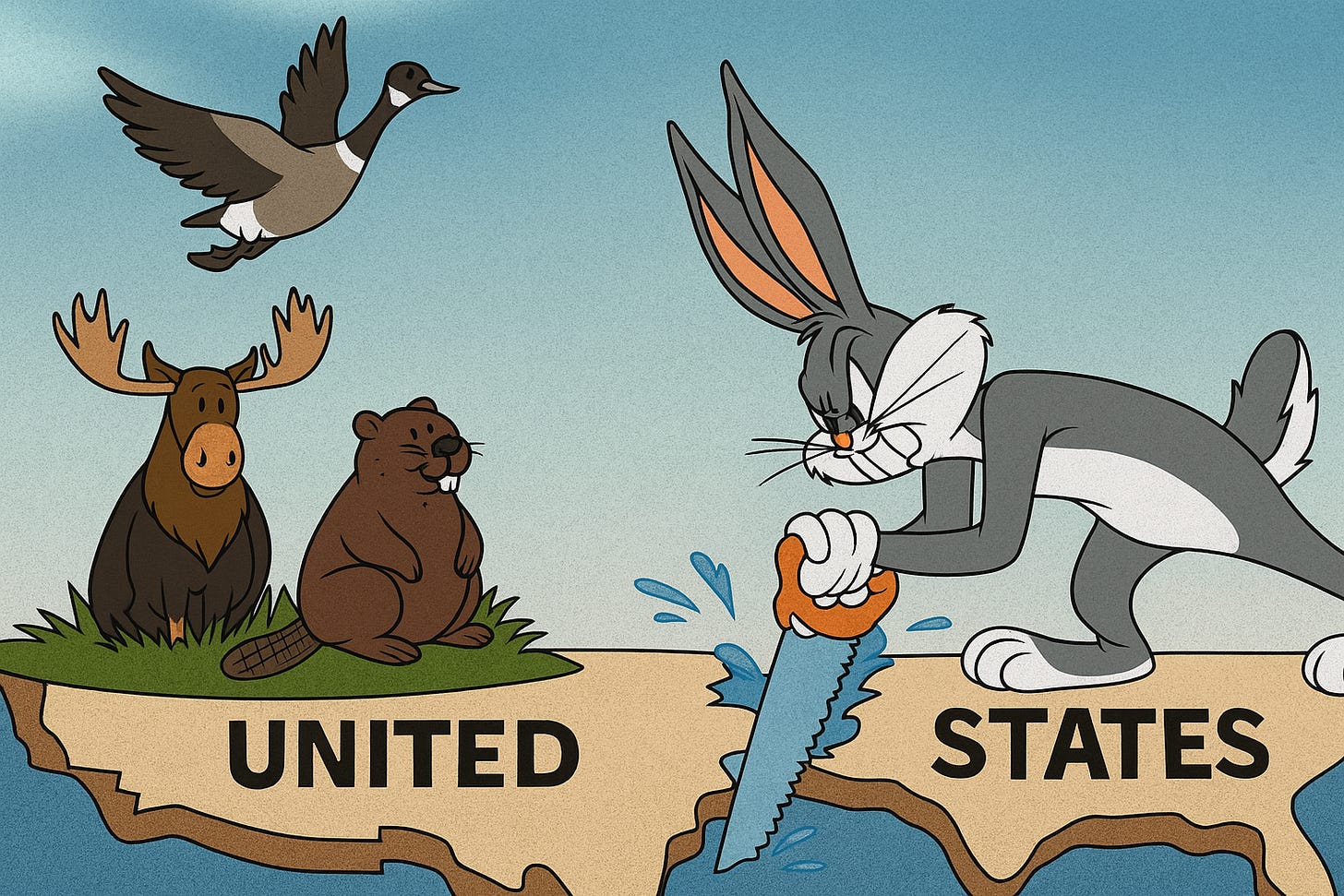

“Nasty” Is One Word for It. Effective Is Another.

How Canadian Consumers Quietly Redefined Economic Resistance

When U.S. Ambassador to Canada Pete Hoekstra addressed the Pacific NorthWest Economic Region (PNWER) Foundation conference in Bellevue, Washington, from July 20-24, his comments landed with more force than perhaps he intended.

Apparently, we’re “nasty.”

That was the word used this week by U.S. Ambassador Pete Hoekstra to describe Canadians who are pushing back against Trump-era trade bullying by staying home, skipping the cheap beer run, and thinking twice before booking a border-hugging vacation.

“Canadians staying home, that's their business, you know. I don't like it, but if that's what they want to do, it's fine. They want to ban American alcohol. That's fine,” Hoekstra said, when asked about slumping tourism ahead of next year’s FIFA World Cup matches in Vancouver and Seattle. Then came the kicker:

“There are reasons why the president and some of his team referred to Canada as being mean and nasty to deal with.”

British Columbia Premier David Eby wasn’t having it. In a blistering response, he said Canadians’ quiet consumer resistance is clearly working—and that Hoekstra’s frustration only confirms its impact. “Keep it up,” he said.

For many Canadians, this wasn't just another headline. It felt like a slap. And maybe a challenge. Because for months now, millions have been quietly adjusting their habits—avoiding U.S. goods, shifting travel plans, and buying Canadian alternatives, not out of ideology but out of something more visceral: fatigue, insult, and refusal.

Referring to Canadians who had stopped buying American products and cancelled travel plans to the United States, Hoekstra — who assumed his current post as Ambassador on April 29, 2025 — remarked that they were being “mean and nasty.” The charge was delivered with the tone of a throwaway grievance, but the setting—an international trade forum attended by premiers, business leaders, and policymakers—made it clear: this wasn’t just rhetorical theatre. It was a diplomatic tell. Yes, it was also pure parroting of Trump’s talking points about ‘nasty Canadian negotiators.’ You know the ones. The ones who negotiated CUSMA—the new NAFTA that Trump signed and boasted was the best deal ever, a deal he now increasingly feels cheated by.

Hoekstra’s doubling down on the ‘nasty Canadians’ comment signalled that something Canadians have been doing had worked. Not government-to-government pressure. Not retaliatory tariffs. Not some centrally orchestrated campaign. What had worked was quiet, broad-based consumer behaviour. Ordinary Canadians, with no official leadership, had collectively altered the economic conversation between Canada and its largest trading partner.

This is worth taking seriously. Because it’s not just a story about bourbon and border shopping. It’s a story about the reassertion of Canadian economic agency—and the emergence of a new kind of trade politics from below.

A Quiet Rebellion

It began, fittingly, in winter. In a bitterly cold February 2025, amid a new wave of tariffs, U.S. economic threats, and openly antagonistic language about Canada’s industrial policies, something shifted. Then came the insult that lit the match: a U.S. official musing—publicly—about Canada’s place in the world as "essentially a 51st state." It wasn’t just belligerence anymore; it was ownership. Entitlement.

Canadians didn’t rally. They didn’t burn flags. They didn’t need to. Better tools were available.

Instead of performative protest marches, they quietly redirected their spending. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau had urged Canadians to stand strong and “choose Canada”—not just in words, but at the checkout aisle. “It might mean checking the labels at the supermarket and picking Canadian-made products,” he said in February 2025. “It might mean opting for Canadian rye over Kentucky bourbon, or forgoing Florida orange juice altogether.”

But by then, the shift was already underway. A cross-country mood had taken hold: one of frustration, fatigue, and refusal. Consumers began swapping American goods for domestic or third-country alternatives. Spirits. Groceries. Personal care items. And, crucially, vacations.

Data from the Bank of Canada's Canadian Survey of Consumer Expectations (CSCE) in late May 2025, for instance, revealed "a notable dip in its new consumer sentiment indicator, reflecting more cautious attitudes about spending, jobs, and finances" and pushing "more Canadians to buy local products and opt for domestic trips" (Finimize, July 21, 2025). This followed earlier reports from Leger in February 2025, which found that "approximately two-thirds of Canadians have reduced their purchases of American products, both in stores (63%) and online (62%)" (Leger, February 21, 2025). By April 2025, a study from NIQ confirmed that nearly half of Canadians were "opting for domestically made goods, even at the expense of convenience or cost," with this "surge in patriotic shopping" reshaping purchasing behaviour in categories from beer to BBQ sauce (Grocery Business Magazine, May 21, 2025).

The impact was swift and tangible:

Canadian visitation to the U.S. dropped significantly. Statistics Canada reported a 31.9% year-over-year decrease in Canadian-resident return trips from the United States in May 2025. This included a 37.4% decline in automobile trips and a 17.4% decrease in air trips from May 2024 levels (Statistics Canada, July 23, 2025). The U.S. National Travel and Tourism Office now projects a substantial drop in overall Canadian travel to the U.S. in 2025, contributing to an estimated $25–29 billion fall in total international tourism to the U.S. this year (Statistics Canada, June 25, 2025).

(While specific comprehensive figures for U.S. spirits sales are still emerging, the broad trend aligns with this caution. Preliminary reports suggest a marked preference for domestic or third-country alternatives)

This was not a campaign. There were no flyers or early-stage coordination. Just a steady, distributed withdrawal of economic attention from a neighbour perceived as no longer friendly. It was trade diplomacy without a press release—and it caught American officials off guard.

By March, what began as a quiet consumer shift had found its own signal: #ElbowsUp. Not a slogan cooked up by strategists, but a phrase that captured something proudly Canadian—unapologetic, practical, and quietly defiant.

Not a Boycott—A Boundary

Hoekstra’s comment at PNWER revealed more than just diplomatic tone-deafness. It demonstrated a lack of understanding about what Canadians were actually doing.

This wasn’t about punishment. It wasn’t about anger. It wasn’t, in the traditional sense, even about protest.

It was boundary-setting.

In the absence of immediate effective government leverage, Canadians had chosen the tools available to them: their wallets, their travel plans, their grocery lists. This was not economic nationalism so much as a reassertion of self-respect—a soft and sovereign refusal to continue funding a relationship that had become openly hostile. This was economic resistance without hostility. And it was effective precisely because it was neither centralized nor performative. No grandstanding. Just thousands of small, personal choices accumulating into something undeniably real.

Consumer Power as Civic Action

What we’re witnessing is a form of economic signalling from below—a strategy that has largely been overlooked in traditional accounts of trade relations.

Governments sign agreements. Corporations shape supply chains. But consumers? Consumers are usually framed as downstream actors—reacting, not shaping.

This moment challenges that.

When Canadian consumers stopped buying American spirits and rebooked their vacations closer to home, they didn’t just withhold money. They sent a message: that trade isn’t just about goods. It’s about trust. About stability. About reciprocal respect.

And while political leaders from both countries continue to meet behind closed doors, trying to paper over fractures and reestablish calm, it is consumers who have already acted—decisively and in coordination, without needing to coordinate. That is not just resistance. That is power.

Why This Moment Matters

There’s a temptation to dismiss consumer movements as short-term or symbolic. But this isn’t a flash-in-the-pan boycott. This is a correction. And it may be a preview of something larger.

As global trade becomes increasingly politicized—and as authoritarian powers use economic coercion as a tool of statecraft—smaller democracies will have to find new ways to push back. Tariff-for-tariff games won’t be enough. Nor will top-down deals negotiated at a glacial pace.

What this moment shows is that distributed, values-driven consumer behaviour can apply meaningful pressure where traditional levers fail.

And in the Canadian context, it also signals something else: the end of complacency in our relationship with the U.S. For too long, Canadian economic identity has been shaped in reaction to American policy—passive, deferential, and dependent. What this moment suggests is that those habits are breaking. That Canadians are learning, at the grassroots level, that sovereignty isn’t just a matter of borders and military procurement. It’s also a matter of breakfast cereal, air miles, and brand loyalty.

Call It What You Like

You can call it nasty, if you like. You can sneer, as Hoekstra did, and mock the consumer choices of your closest ally. But if you do, you reveal the very fragility this behaviour is responding to.

Because Canadians didn’t escalate. We didn’t threaten. We just stopped showing up—and the economic ripples were immediate. This is the most Canadian resistance imaginable: peaceful, effective, and deeply polite. But it’s also unapologetic.

And if that bothers those who wish to dominate, not cooperate—then perhaps “nasty” is just another word for sovereign.

Strategic Nuisance: When Consumer Pressure Meets National Policy

It’s tempting to view consumer-led resistance—like ABUS shopping or boycotts—as separate from formal government policy. But what’s unfolding right now suggests something far more coordinated, even if unspoken. Call it parallel pressure. While individual Canadians are quietly choosing alternatives to U.S. goods, the Canadian government appears to be doing the same—only at the scale of entire economies.

Indeed, reports from July 2025 indicate that Canada and Mexico are "closing in on a scheme to bypass the US to reduce transhipment tariffs and taxes and boost trade between them," an initiative informally dubbed the 'Northern Corridor' or 'North Belt' (The Loadstar, July 21, 2025) This ambitious project, expected to be fully functional by 2028, aims to facilitate direct trade between Canada and Mexico, with the explicit goal of reducing reliance on U.S. territory, infrastructure, and policy volatility.

What the Corridor Means in Practice:

Bypassing U.S. Ports and Policies: The Northern Corridor is being designed to move goods without touching U.S. soil—cutting out U.S. border crossings, port authorities, and warehouses. This means fewer transshipment taxes and tariffs, and far less exposure to unpredictable U.S. trade policy shifts.

Maritime, Rail, and Digital Integration: The agreement is ambitious.It includes new maritime links between eastern Canada and the Gulf of Mexico via the St. Lawrence Seaway, west coast routes using Prince Rupert, and a long-term vision for direct rail links. Even digital customs systems are in the works, with blockchain-led “risk-free lanes” that could become a model for frictionless North American trade (The Loadstar, July 21, 2025).

Targeted Sectors: Unsurprisingly, this initiative focuses on goods that have been caught in U.S. crossfire: steel, auto parts, and increasingly, green economy goods like EV components and batteries.

Economic Impact: Initial projections value the corridor at $120 billion. But the real sting might be to the U.S. economy. The Loadstar further notes that this corridor could see a "big numbers" impact, with one estimate suggesting a "$245bn hit [to the US] over five years" through redirected trade (The Loadstar, July 21, 2025).This aligns with the long-standing and growing bilateral trade between Canada and Mexico, which reached nearly $56 billion in two-way merchandise trade in 2024, with Mexico serving as Canada's third-largest single-country merchandise trading partner (Global Affairs Canada, July 18, 2025).

Timeline: Construction and coordination have just begun, but the corridor—sometimes referred to as the North Belt—is expected to be fully operational by 2028 (The Loadstar, July 21, 2025).

This isn’t just trade policy. It’s quiet defiance—structured, systemic, and meant to last.

Parallel Pressure: It's Not Just About Cleaners and Toothpaste

What makes the timing of this initiative especially potent is that it mirrors what’s already happening at the consumer level. Canadian shoppers are increasingly asking hard questions: Who made this? Where did it come from? Why does my purchase feed someone else’s leverage over my country’s economy? Those aren’t theoretical concerns anymore. They’re animating spending choices and quietly shifting market share.

In that sense, the Northern Corridor is the macro version of ABUS shopping. Consumers are applying pressure from the bottom up. Governments are reinforcing it from the top down. And between them? A middle space where markets start to shift, retailers start to adapt, and suddenly what was once just symbolic becomes strategic.

This is the time for Canadians to double down on supporting Canadian small- and medium-sized enterprises. It’s time to help turn start-ups into scale-ups, and domestic alternatives into dominant players. Because one thing we know for sure: Donald Trump won’t back down until both MAGA loyalists and mainstream Democrats finally scream “enough.”

I live in Ontario — and we know how costly, and how grinding a recovery can be, when you're stuck riding out the nightmare of a bad majority government. As much as I feel for the American businesses now hurting from the quiet withdrawal of Canadian dollars—from tourism, from grocery imports, from everyday consumer goods—we didn’t elect the Trump administration. Their pain is real, but so is our right to protect ourselves from being treated as economic pawns.

If this is what nasty looks like, maybe it's not so nasty after all. If the Northern Corridor is any indication, “nasty” might just be another word for strategic. For the Trump administration and its economic nationalists, “nasty” simply seems to mean Canadians understanding our own worth—and standing up for it. Whether it’s with our wallets or our trade routes, we’re learning to say: we have other options.

This article reflects trends and developments observed through mid-2025, including consumer polling, trade data, and media coverage from sources such as Leger, StatCan, The Loadstar, and others. As we all sadly know, in a world that has Donald Trump twitch-dancing through news cycles, much can change before year’s end.

If you found this valuable, consider supporting my work—one quiet cup at a time. ☕

🎁 Support the work, fuel the next one.

If you downloaded this resource or shared this post—thank you. If you’d like to help keep this kind of content coming, you can support Between the Lines with a coffee or a paid subscription. Every little bit keeps the wheels turning.

This piece first appeared at Between the Lines, my home base for longform writing, analysis, and commentary. If you’d like to read more like this, feel free to visit or subscribe there as well.

ABUS shopping and travel boycotts are acts of personal agency by individual Canadians. These behaviours appear to holding up. Hopefully, they will become a habit (Î still boycott California grapes and US wine). Canadians have a desire to act personally and directly - think of refugee sponsorship groups. I hope the federal and provincial governments will facilitate other avenues for personal action. One possibility is some form of targeted Canada Savings Bonds - housing, infrastructure or perhaps even defense equipment. Î known this instrument was discontinued because it was no longer efficient or effective but I think there is value to have an avenue for Canadians to make a direct financial contribution within their means. It’s all about individual agency.

You have taken a balanced approach to the North Corridor discussions. It will be interesting to see how this plays out and I wonder if these measures may also position Canada to increase trade to Central and South America.

Voting with your dollars is a very powerful tool. might not think individually that it's powerful, but you multiply that by say four or five million people adds up. Some things we can't buy Canadian, but for the other 90% that extra 5% to buy the Canadian product is worth it.